Tom Fleischner & Ed Grumbine

The practice of connection

THEMES: Personal Practice, Society | WORKSHOP: Natural History & Society

Biographies

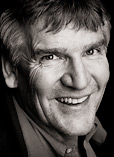

Tom Fleischner

Tom has been on the faculty of the interdisciplinary Environmental Studies Program at Prescott College for 23 years, teaching natural history, conservation biology, and a variety of courses that link natural sciences with humanities and policy. Before that he co-founded the North Cascades Institute in Washington. Tom is the founding President of the Natural History Network and lives in the Ponderosa Pine-covered Central Highlands of Arizona, ranging from there to the Gulf of California, the Gulf of Alaska, and the Gulf of Maine, as well as the Pacific Northwest. He has written about the relationship of people and nature in a wide variety of journals and magazines, and in three books: Singing Stone: A Natural History of the Escalante Canyons; Desert Wetlands (a collaboration with photographer Lucian Niemeyer); and as editor of the new anthology, The Way of Natural History.Conversations:

Workshops:

Ed Grumbine

Ed Grumbine teaches in the undergraduate Environmental Studies Program at Prescott College, Arizona. He has worked on biodiversity protection on federal lands in the U.S. for over 25 years and is known for contributing to ecosystem management. Since 2004, Ed has focused on conservation in China. He currently is a 2010-2011 visiting scholar at the Centre for Mountain Ecosystems, Kunming Institute of Botany (Chinese Academy of Sciences). Ed is the author of Ghost Bears: Exploring the Biodiversity Crisis (Island Press, 1992), editor of Environmental Policy and Biodiversity (Island Press, 1994), as well as many papers on conservation and development. His new book, Where the Dragon Meets the Angry River: Nature and Power in the Peoples’ Republic of China was published in spring 2010.Conversations:

Workshops:

Transcript

Ed Grumbine: One of the bedrock delights of my friendship with you over the years has been the reciprocity that has been so evident for both of us in our professional practice of natural history, and certainly are private friendship. Because of you, my sense of isolation has never developed greatly, and I want to thank you for that.

In this group the theme of isolation has popped up everyday, multiple times. It's interesting that as someone focused on nature and dwelling in the big community of things that many of us still feel isolated. I've never felt that. Not certainly just because of our friendship and are mutual practice together, but that's certainly a big piece of it. I don't have to think too much about compadres. I'm living in a separate country right now, and a separate culture, language, etcetera. I have nobody to practice natural history with. Yet, I'm still not isolated, and I don't feel that sense of isolation as much as others of our group, who are embedded in the same continent, if not the same community, have expressed.

I'm curious about your take on being in community, feeling isolated, or not, and how that cycles back to both your personal practice of natural history, as well as the social aspects of that.

Tom Fleischner: I think every person needs to have a sense of community. I wouldn't look at the world in the same way – and I mean that not metaphorically but literally – if it hadn't been for our friendship. And central to that friendship is what we have shared in terms of natural history. We literally became friends identifying flowers together. And that's continued ever since. It is interesting what you're saying about the sense of isolation people are feeling here, because the whole practice of natural history is about feeling a sense of connection with all of the beings around us, human and otherwise. So it's somewhat paradoxical, perhaps, that people would feel a sense of isolation through the practice of connection.