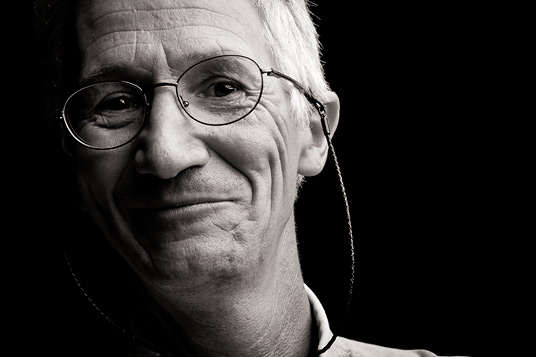

Carlos Martinez del Rio

The fruiting bodies

THEMES: Challenges & Opportunities, Definitions, Society | WORKSHOP: Synthesis

Biography

Carlos Martinez del Rio

Carlos Martinez del Rio grew up surrounded by cow dung and books. In the morning he chased cattle and at night he read. He discovered natural history through W. H. Hudson, Dersu Uzala, Gilbert White and Horacio Quiroga. He learned about nature on horseback and through the stories of old vaqueros. After the family ranch was sold he became a beach/mountain bum but found the bumming life incomplete. A Ph.D. allowed him to make a living as a naturalist that teaches science. He has a disorganized and catholic love for wild creatures. He has explored how phainopeplas disperse mistletoes, why hummingbirds can digest table sugar but robins cannot, and why temperature makes hawkmoths uncertain pollinators. Most recently, he learned how to count neutrons with a variety of big and rather ugly machines to find out how much white-winged doves depend on saguaros and why there are so few marine songbirds. By accident rather than by inclination, he has become a cyborg naturalist that expands his very limited human umwelt with a variety of cutting-edge technologies. However, his technophilia is tempered by the conviction that it is only by being outside (cold and hot, dirty and exhausted), in proximity and relationship with wild, feral, and domestic fellow creatures that he can become wiser and be happy. The isotopic composition of his body is that of the land where the mountains meet the prairie. He lives in Wyoming.Conversations:

Workshops:

Transcript

The argument I would like to pose to you is that natural history is a bit like mycelial fungus. It has been in the forest all the time with very healthy mycelia, we just didn't see the fruiting bodies. And when there's a good rain that requires syntheses, which is the moment we are in, then the fruiting bodies come up and you can see them.

Natural history has never disappeared. The mode of science that we do has never disappeared. It's just that now, it's like the end of the 19th century; it's a lovely time for the fruiting bodies to come up and to be exposed again. Natural history was not dead. It was just proliferating in the litter.